For miners of the Acquisition Mine, each trip down meant money coming up.

News reports from the time record that the output from the mine would increase during each trip into the belly of the mine. Ore found below was of “first-class quality” and went for $100 to $200 per ton.

With the estimated amount of 1,000 tons of base ore, the Acquisition Mine was the definition of the American Dream.

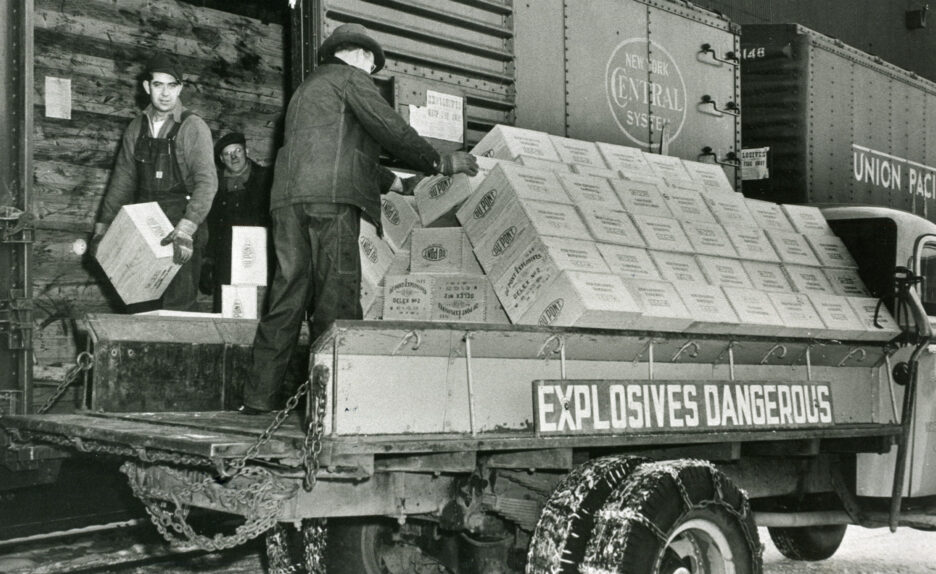

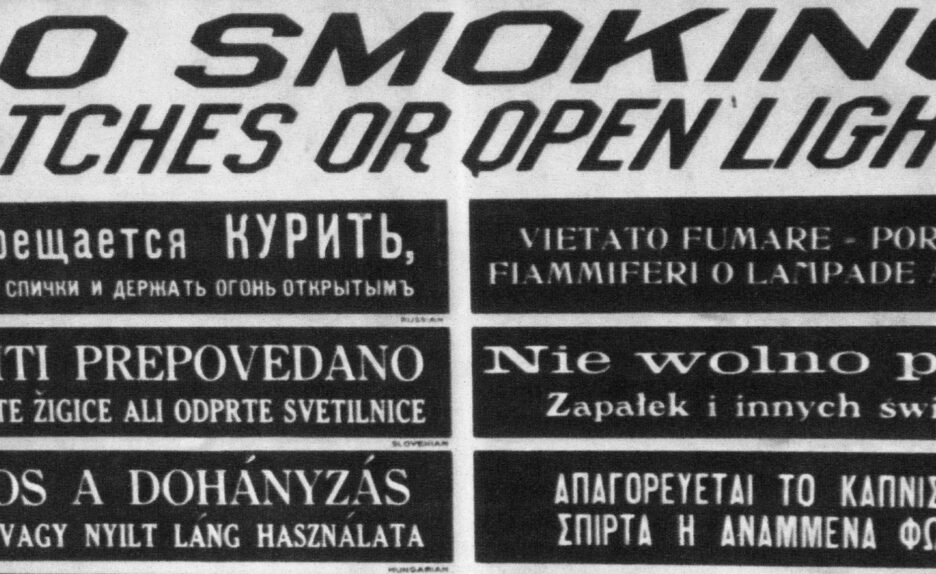

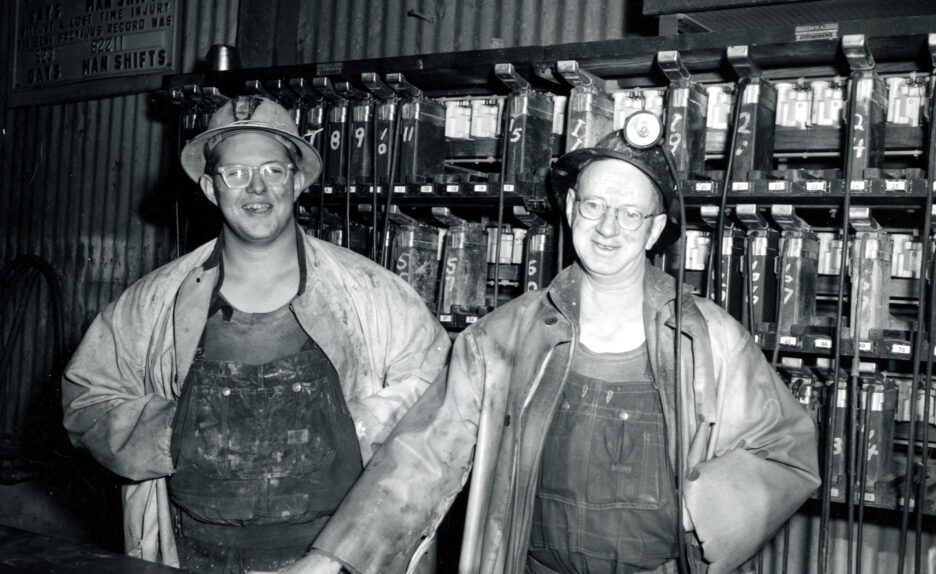

With signs being translated in 17 languages, immigrants played an integral role in the building of Butte’s diverse history.

For travelers in search of a better life, it was found in every ton of ore pulled up-and the Acquisition pulled up a lot.

Photos provided by the World Museum of Mining

Even though we can’t make a Canadian Whiskey here in Montana, we can acquire one. We take the Canadian Whiskey and age it in red, white and bourbon barrels, before blending them together. Breathing life into a new melting pot-our Acquisition Canadian Whiskey.

For people across the world, Butte stood as an inspiration. It was a place of opportunity where people where people could, and did, strike big.

The Acquisition Mine is no longer standing, but the lasting impact is felt our Butte Community. Through the people who care for the city and continue to keep finding riches in it every day.

Nestled on the west side of town, away from the other mines in Butte, the Orphan Girl Mine found its home in 1875.

But the mine struggled throughout its life. Changing hand multiple times and even flooding during a lengthly legal dispute over ownership which ceased mining.

By 1944, miners removed over 7 million ounces of silver from the Girl’s depths. A small amount in Butte standards. In 1956, the Girl sat abandoned and never ran again.

Ten years later, the World Museum of Mining was born around the Orphan Girl Mine. Preserving the grounds, items and artifacts in a time capsule of Butte history. When you walk through the doors of the World Museum of Mining, you step back in time as a visitor of what Butte used to be.

Photos provided by the World Museum of Mining

Headframe understands that the work the Museum does for the Community and our history is important. That’s why we made a spirit dedicated to them.

Our Orphan Girl Bourbon Cream Liqueur continues that smooth transition that you feel each time you transcend through the doors at the World Museum of Mining and down into the cold of the Orphan Girl Mine.

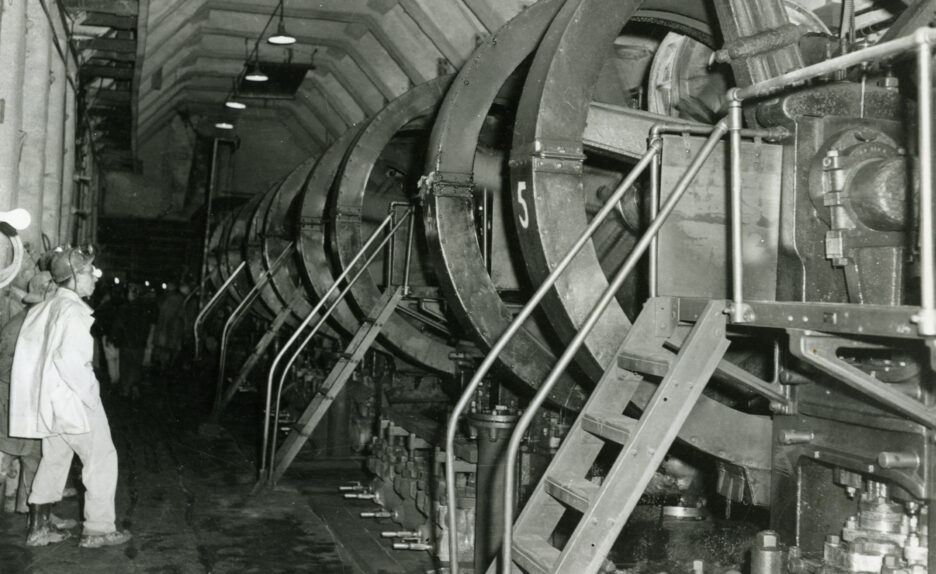

While the Museum is a walking tour now, miners recount how the 3,200 feet ride to the bottom took ten minutes by hoist. A depth no longer accessible due to ground water flooding that has filled most of the mine shaft.

We love the World Museum of Mining. Their photo archives, their Hell Roarin’ Gulch tour of old buildings and artifacts. And we really love their underground tour which takes you 100 feet underground at the Orphan Girl Mine. This tour is a must do stop on any travel to Butte. It’s a great way to build understanding for what it was like for miners working underground.

During its operation, the High Ore mine was a strong producer of high quality ore pulling minerals like quartz-pyrite from its veins. It was during this time that Butte became known as “The Richest Hill on Earth.”

“The [High Ore] vein filling consists of quartz arid pyrite, with enriching bornite and glance, the richest

streaks being near the footwall,” writes the United States Department of the Interior. “The usual abundance of fault clays and slips of other veins is lacking, and the ore shoots end abruptly in lean quartz and pyrite.”

The high quality ore pulled from the ground had a purity rarely found in Butte mining history.

We know that high quality is hard to find, in the ground and in the glass – that’s why we chose to name our spirits High Ore Vodka. We want a high quality, pure distillation and just like those miners, we’ve found it.

Photos provided by the World Museum of Mining

Historically, the High Ore served another purpose too.

Working with the Kelley, both mines pumped ground water out of the mines at rates of around 5,000 gallons per minute. Because most of the underground workings were interconnected, not every mine needed to pump water out itself. Instead, they relied on larger mines like the Kelley and the High Ore to do the work. It was necessary work to allow miners to reach deeper veins.

Studies of the High Ore Mine found, “large high-grade ore as deep as 2,800 feet.”

These claims created hope for the miners. Digging down deeper and deeper, their efforts were rewarded with pure ore. A reminder of what is possible for hard workers everywhere.

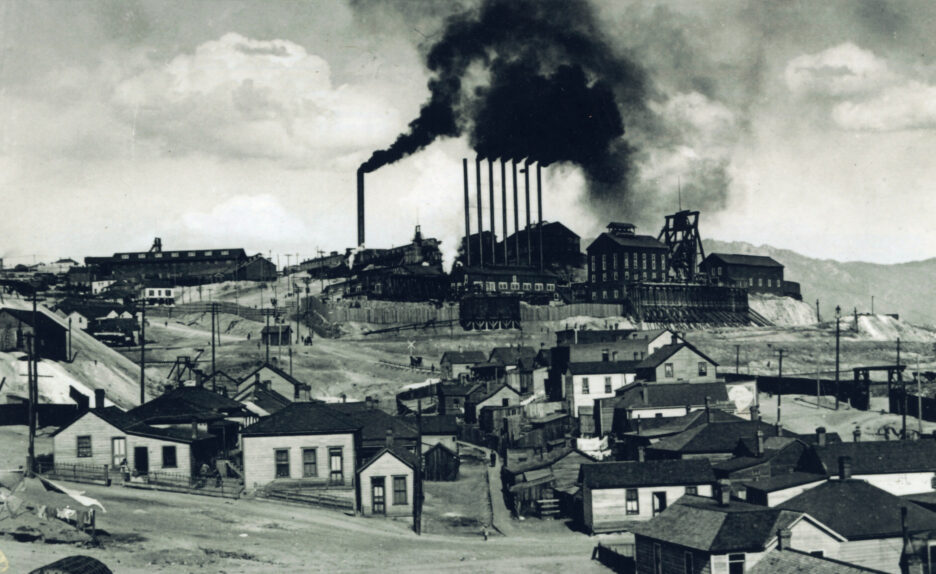

Boat horns echo along the shore line as they pull up to dock. It’s Ellis Island, New York 1910.

Waves of immigrants step off the boat and onto the docks, met by officers who send them on their way. Some have a family name and some have nothing. Others arrive with a photo or a note pinned to their shirt.

“Send me to the Seven Stacks of the Neversweat.”

The infamous, visually striking image of the Neversweat Mine breaks language barriers. For many, it represents hope. A beacon for people around the world that a better future is out there.

They found that future here – in Butte, America.

“Those folks who finally made it here don’t know exactly where they’re going, but they’re hoping for the best,” says Headframe Co-Owner Courtney McKee.

Photos provided by the World Museum of Mining

What began as one of the cooler mines in Butte eventually soared to high temperatures and lower depths as its popularity grew. The richness of its caverns and the heat from below can be experienced in every sip of our Neversweat Straight Bourbon Whiskey where we unlock deeper characters from the mine in each glass.

“You could never understand how hot, how humid it would be in these [mines],” recounted Dinny Murphy in a 1986 interview. Murphy detailed moments where they would wring out shirts and pour sweat from out of their helmets.

While hot, miners like Murphy noted that this was not enough to change their love for working in the mines. The love for unlocking something deeper than themselves.

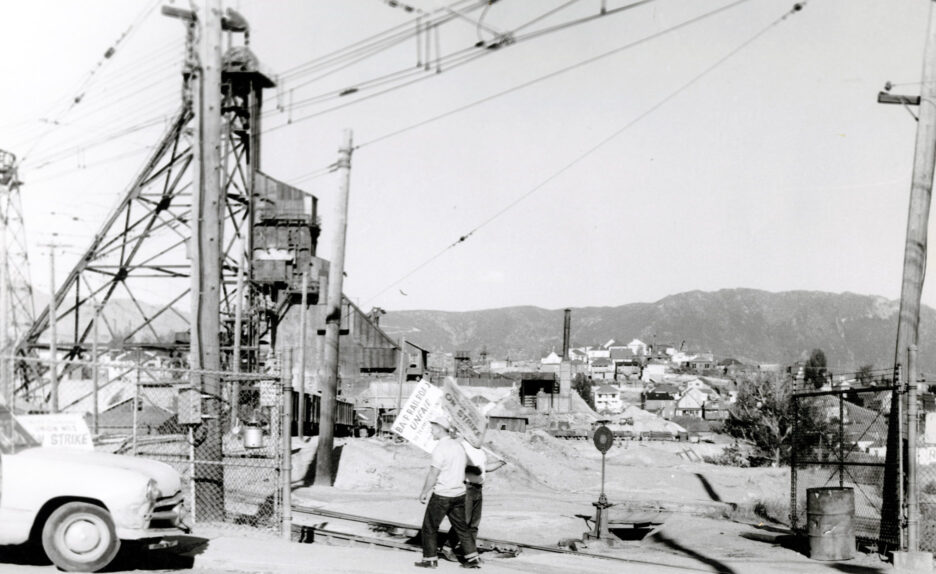

In 1887, the Anselmo Mine first felt the movement of life above and below ground powered by electricity and innovation.

Everyday, they pulled lead, zinc, silver and copper from its veins under Montana Street.

The concept of this diverse combination found within the ore reminded us of gin and eventually led to our product, Anselmo Gin. Just as the miners found riches at depths over 4,000 feet, we also reached deeper to come up with a blend of 10 botanicals to create a one of a kind gin that lives up to its namesake.

August 19, 1959 – workers at mines across the Butte hill went on strike against the Anaconda Copper Company after negotiations regarding better conditions failed. It took 181 days for negotiations to settle. The second longest strike in Butte history. But closing for six months, this strike shut down the Anselmo permanently.

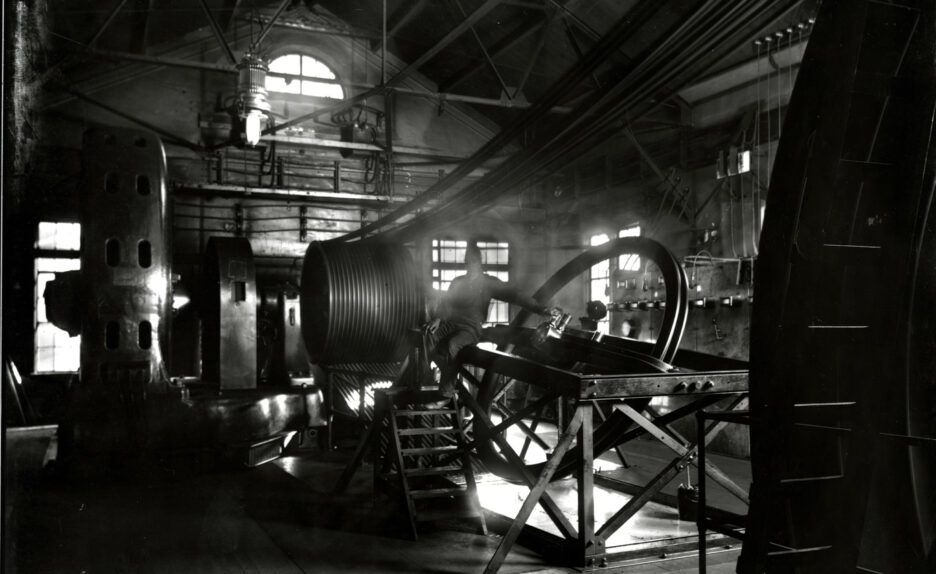

Photos provided by the World Museum of Mining

Now, it sits as the best preserved mine space in Butte. Often a must-see stop for historical tours or anyone visiting town as the National Park Service noted, “the Anselmo Mine yard in particular offers an impressive array of preserved mine yard structures.”

Bells and pressurized air still work in the building and are used as the hoist house in our 2014 film, “The Orphan Girl.”

“With buildings representing the full range of mine yard activities, the Anselmo is a monumental testament to Butte’s mining history and the daily experience of the thousands of mineworkers that powered the industry.”

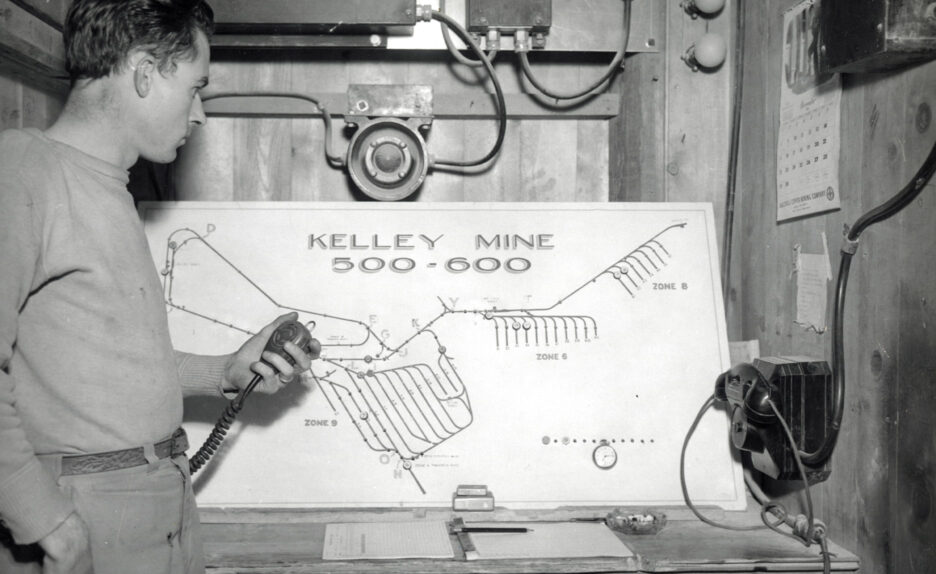

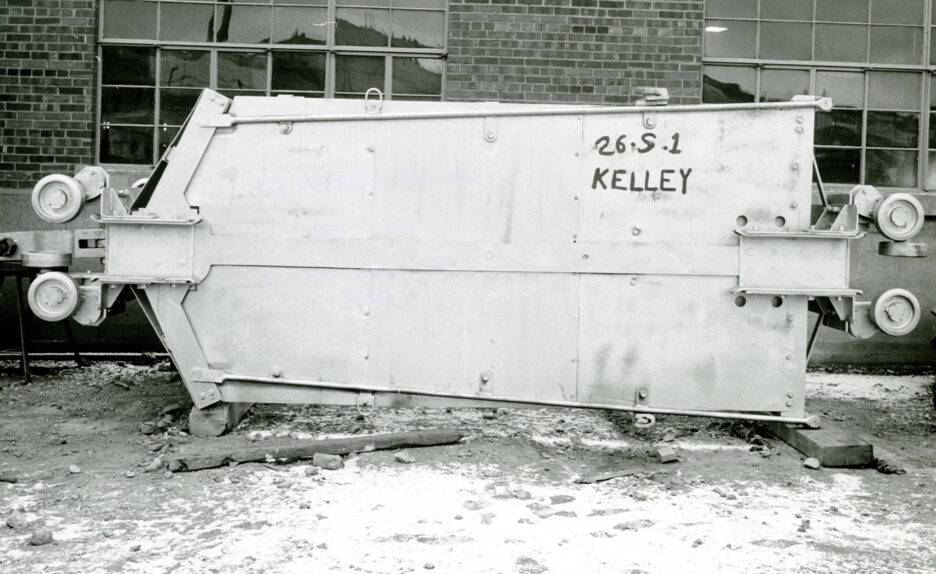

Cornelius Francis Kelley came to Butte, MT from Mineral Hill, NV in 1883 at the age of eight. He worked as a water boy on the Butte Hill and part time as a nipper–essentially, a delivery boy of machinery to the miners–underground at the Anaconda Mine.

It wasn’t long before he worked in the engineering department and worked his way up the corporate ladder. In 1918, Kelley got the name “Mr. Anaconda,” by holding the title of President for the Anaconda Copper Mining Company.

By 1949, Cornelius opened the Kelley mine when the demand for copper increased after World War II. He saw this as the adaptive solution to the economic conditions at the time. Towards the end of its life, it was the last underground mine still in operation before closing its shafts in 1974.

Photos provided by the World Museum of Mining

Today, the Kelley is home to Headframe, where we write our own adaptive reuse success story.

Headframe took over the buildings, which were once mine offices and mining equipment machine shops, and is adaptively reusing them for spirits production, barrel storage and still manufacturing. By bringing manufacturing and innovation back to the Kelley, we help breathe life back into these old buildings and jobs back into our Community.

Headframe came up with the inspiration for the Kelley Single Malt Whiskey in 2010, with no idea that we would one day settle in right here ourselves in 2016. The goal? To honor the brave, Irish immigrants who worked below the ground with an Irish style Whiskey above it.

Now we are doing just that.

The Kelley was once a site where men gathered, risking their lives for their livelihood. Today, Headframe honors them as our team gathers here working to create something new, born from the respect of our past.